Create DoDAF views and produce reports in seconds

Visual Paradigm provides an easy-to-use, model-driven solution that supports the development of DoDAF 2.02 views and models. Create integrated DoDAF products that maintain traceability between views. Generate architecture documents that facilitate organizations to effectively coordinate enterprise architecture initiatives.

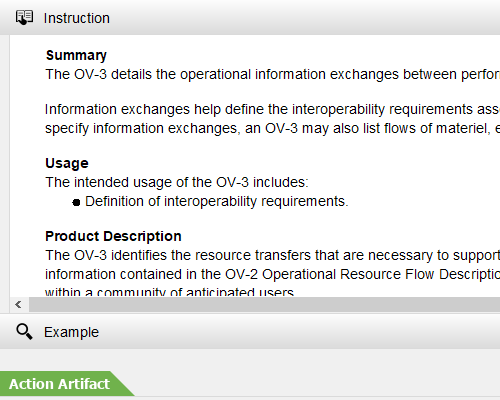

DoDAF's grid representation provides a logical way to manage building products. Architects can easily access a specific view through this interface.

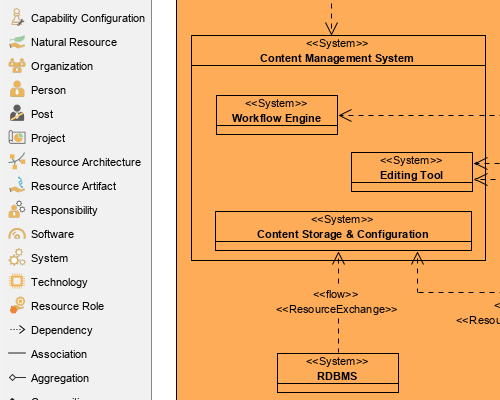

Visual Paradigm extends UML with a new set of diagram types and a new custom diagram toolbar for DoDAF view creation, ensuring that your architecture descriptions conform to DoDAF guidelines and specifications.

Building blocks created in one view can be visualized in any other view by a simple drag-and-drop action. Modifications to a model will result in automatic updates of the same model in all "alternate views".

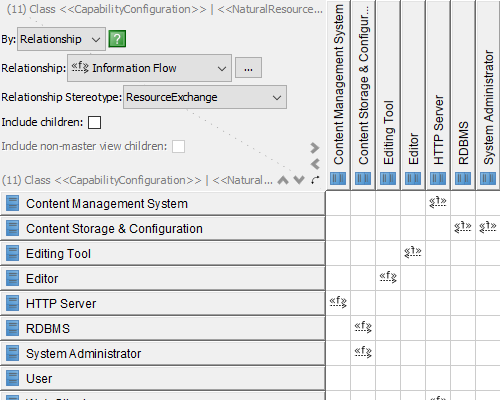

The traceability between architecture components can be visualized using a matrix tool, or an analysis diagram can be used as a visual traceability map.

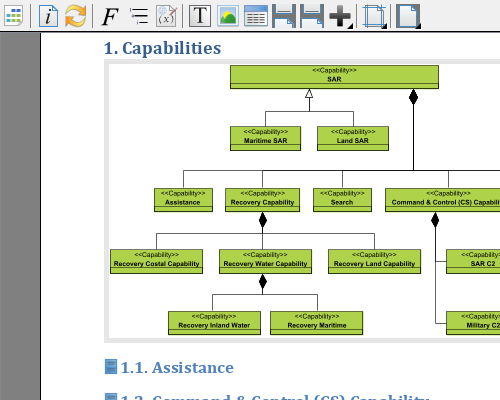

Generate construction documents immediately from the created views and descriptions, or create your own DoDAF reports with the intelligent report generator "Doc. Composer". The documents are automatically archived in a document repository for future retrieval.

You don't need to be a DoDAF guru to create DoDAF products. Just follow our step-by-step guide. You'll be doing the right thing in no time.

The team collaboration feature enables architects to work on the same DoDAF architecture project at the same time, keeping everyone connected at all times.

Visual Paradigm is designed to be a multi-purpose product. Power your projects with UML, BPMN, ERD, DFD, UX (wireframing, prototyping), code engineering, ORM, mind mapping, and more.