Create professional EA models quickly and effortlessly.

Create professional enterprise architecture blueprint quickly and collaboratively using an ArchiMate software chosen by enterprises from all over the world.

Drag. Drop. Done. Enterprise architecture design has never been easier.

From the view of a modeler, the viewpoint feature ensure the creation of model with proper ArchiMate shapes, through a constrained palette shape connection.

Instantly create user-defined shape types with preset definition and formatting.

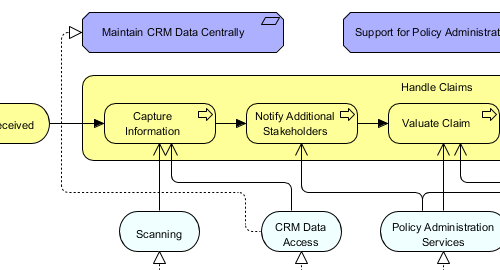

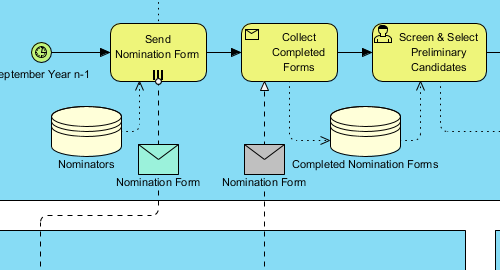

Visualize business workflows with the BPMN tool. BPMN provides a rich collection of simple yet comprehensive modeling symbols that all people, from business analysts to stakeholders can understand.

Create BPMN diagrams quickly with drag and drop. Use the alignment guide to position shapes precisely on a diagram.

Automatically keep the traceability among As-is and To-be model, which is particularly useful in gap analysis.

Intuitively expand a sub-process through a single click, and to browse the BPD at a deeper level.

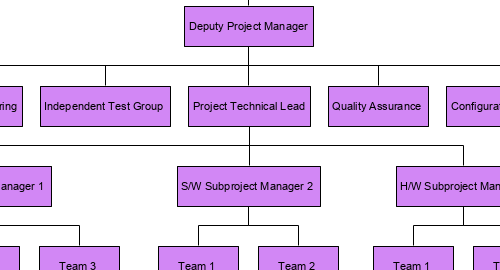

Organization chart is widely used in the development of enterprise architecture model. Here are some of the typical uses:

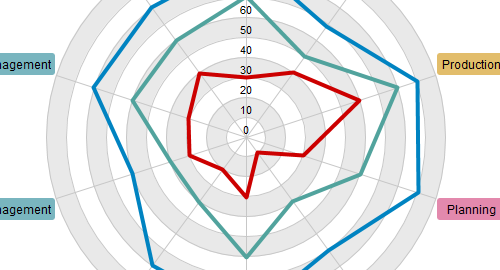

What is the capability level of your development team? Which part of your team requires strengthening or optimization? What is the focus areas that will support your development activities? By drawing a radar chart (a.k.a spider chart), you can easily find answers to all these questions.

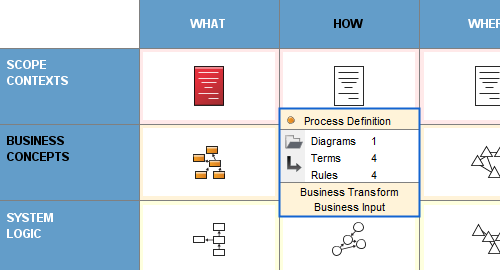

Zachman Framework is a two-dimensional that lets you view, define and specify an enterprise, with six typical communication questions (who, what, where, when, why, how) as columns and six perspectives (scope contexts, business concepts, system logic, technology physics, component assembles and operations classes) as rows.

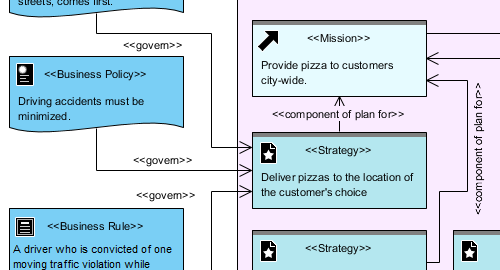

Develop your business plan by creating a business motivation model (BMM). A BMM diagram visualizes the factors that motivate the establishment of the business plans. It also provides a graphical representation of the business plans and shows how the factors are related with the business plans.

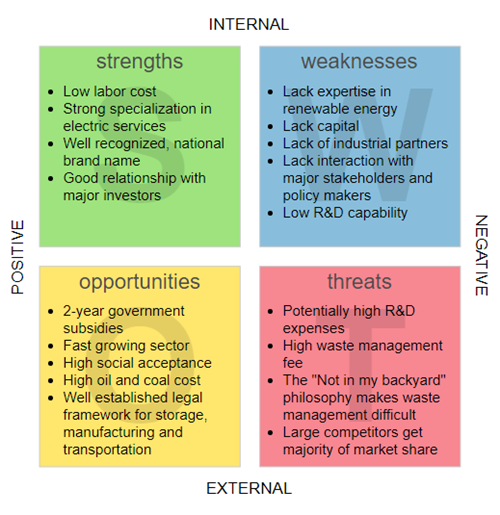

Quickly draw beautiful SWOT, PEST, Value Chain, Five Forces, and other strategic analysis diagrams with powerful strategic analysis tools.

Evaluate the internal and external factors that can influence your business.

List the activities that a business perform to deliver a valuable product or service.

List and assess the constraints or opportunities based on the four kinds of environmental factors.

Identify the five competitive forces that shape a business.

Predict the future moves of your competitors based on your business’s strategic move.